It’s April, and I’m heading as far south as it’s possible to drive in the continental U.S. Passing Everglades National Park, I’ll travel U.S. Route 1 to the 113-mile stretch of Overseas Highway that hops along the Florida Keys.

With the Gulf of Mexico on one side and the Atlantic Ocean on the other, there’s no better place to find hope for the oceans. It’s been a bucket-list trip for me, long drawn by that necklace of islands linked by the famous highway.

On previous trips along America’s East Coast as a travel writer, I connected with people working hard to help the oceans – a shark educator, staff at a turtle hospital, chefs serving invasive species to keep their populations down. I sensed there would be equally hopeful discoveries in the Keys.

I’ve always lived by the Atlantic. Born into a large fishing family, my father harpooned swordfish and netted cod. One grandfather cooked aboard fishing boats; the other ran a wholesale fish business. My mother served seafood more often than not – swordfish steaks, creamed lobster, cod cheeks and smoked haddock. Fish was plentiful, inexpensive and delicious.

Today, I live in Lockeport, Nova Scotia, Canada, a tiny fishing village on what would be an island but for the silver sand beach that connects it to the mainland. My community depends upon the sea, and I’m alarmed at the challenges facing the world’s oceans: overfishing, pollution, warming waters and coral reef bleaching. The drive down the Overseas Highway is a search for hope for my ocean.

Marathon

At mile marker 48 in Marathon, I discover a sign of hope for the oceans in the story of mechanic Richie Moretti, who bought the foreclosed Buena Vista Motel in 1984. It included a saltwater pool, which he promptly filled with fish. Soon, school children were visiting. Because the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles were all the rage, the decision was made to introduce turtles.

The old motel on the side of the road – you can’t miss it – is now The Turtle Hospital with operating rooms, a visitor center, two turtle ambulances and an array of turtle tanks and pools. This is one of 42 turtle rehab facilities in the U.S. alone, a sure sign we’re taking seriously the threat to these lovable creatures.

In small pools, recuperating turtles with names like Tulip and Snuggles painted on their shells swim solo. Some had been injured by boats. Others are sick. At the former swimming pool, a guide passes around food pellets to visitors.

I toss a handful in, and turtles arrive from every corner to gobble up the treats. I’m told I can adopt some of these permanent residents (donate to the hospital in their name), and when the time comes, I can watch as rehabilitated turtles are released into the sea.

Pigeon Key

Retracing my steps a few hundred yards, I grab a rental from Bike Marathon and head off for Pigeon Key via the Old Seven Mile Bridge. Now open only to pedestrians and cyclists, the bridge is what remains of the original Overseas Highway. The new one runs parallel to it.

Chris Rowell, operations director for Pigeon Key Foundation, greets me when I arrive and tells the story of Pigeon Key’s role in the construction of the Overseas Highway. It started when New Yorker Henry Morrison Flagler befriended John D. Rockefeller.

“They decide to start this little company called Standard Oil just as oil goes through the roof, making Flagler rich,” says Rowell. With the opening of the Panama Canal, a tiny backwater 100 miles offshore was about to become a stop on a major shipping route, so he hatched a scheme to build a railway over the ocean to Key West.

Flagler brushed aside doubts he could pull off such an engineering feat and completed his railway ahead of schedule in January 1912. The railway never did pay for itself, and following a devastating hurricane in 1935, it shut down for good. In 1938, the State of Florida turned the railway bed into a road. Repurposed rails are still visible in the old bridge.

I follow Rowell into a cottage where 64 bridge workers once lived. Today, hundreds of buoys hang from the rafters, each signed by a group of visiting students. “We run marine science camps,” says Rowell, “for students from as far away as Alaska and Europe. We teach them about the environment and take them snorkeling.”

Rowell invites me to stay as long as I like, but he has work to do. “My next group – 57 fifth graders – is showing up in 20 minutes. It’ll get real busy, real quick.”

Summerland Key

The farther out I drive, the less familiar things seem. When I reach Summerland Key at mile marker 24, I discover a source of hopefulness beyond anything I could have imagined. Inside the Elizabeth Moore International Center for Coral Reef Research & Restoration, a branch of Mote Marine Laboratory, scientists are regrowing entire coral reefs lost to climate change.

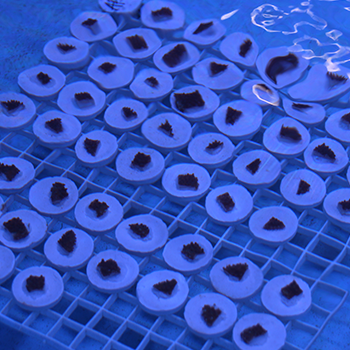

From the outside, the new hurricane-proof research center looks like a giant concrete shoebox on legs. Beside it, dozens of shallow pools hold thousands of tiny corals.

Director of regional operations, Allison Delashmit, guides our group through labs filled with aquariums and tabletop pools. Scientists in T-shirts sit on the floor, scrubbing tiny bits of coral with toothbrushes. Others are slicing larger bits on band saws or creating computerized 3D images of the ocean bottom.

Mote scientists reproduce corals in two ways. First, they clone and grow corals much faster than in the wild. A slow-growing coral might take 25 to 100 years to sexually mature. Mote achieved the same in outplanted coral in a matter of about 5 years. Second, they sexually reproduce corals right in the lab using specimens selected for their ability to adapt to changing ocean conditions.

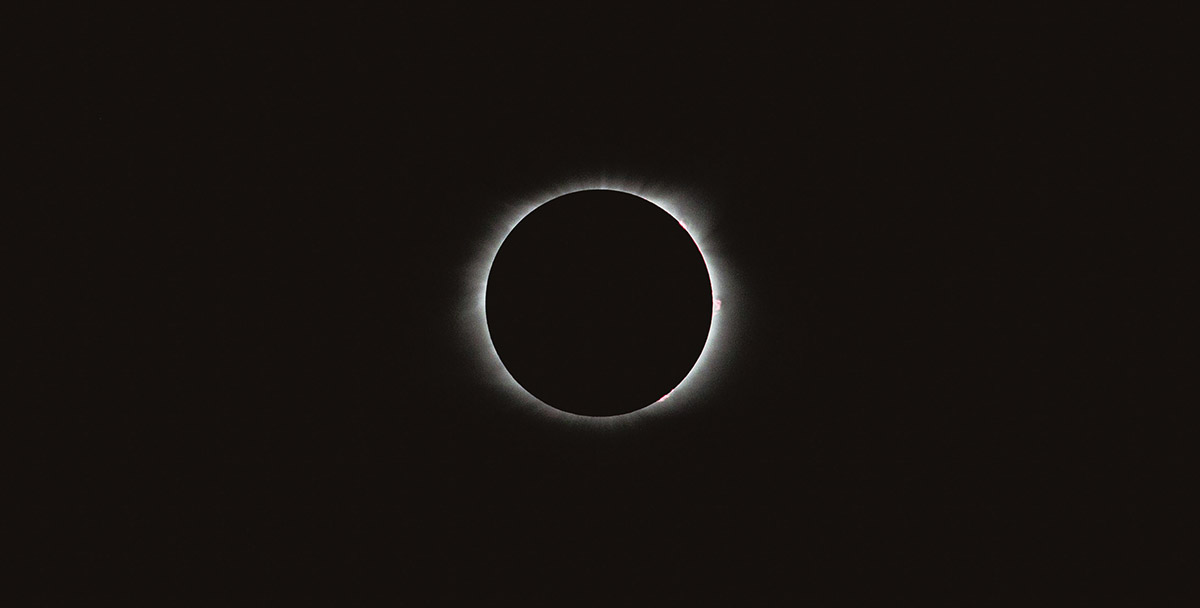

“Corals spawn in August around the full moon when they release bundles of polyps that rise to the surface,” says Delashmit in the coral nursery. “It looks like reverse snow in the water. As soon as they hit air, they break open to reveal eggs and sperm, which have 20 minutes to an hour to find another egg or sperm.”

Coral restoration efforts are underway in 56 countries, so urgent is the need. Mote stands out for its methodology and its goal to quickly repopulate the reef with genetically diverse corals resilient enough to survive threats from human activity.

Delashmit tells me that Mote has planted 174,000 corals on Florida reefs with a survival rate over 90%, helping reestablish reefs that serve as nurseries for sea life and protect the Florida Keys from the ravages of increasingly powerful storms. By the end of the tour, I’m overjoyed with a sense of relief for the future of the oceans.

Key West

I end my Overseas Highway pilgrimage at mile marker zero in Key West with the feeling I’ve come full circle. On the Southernmost Food Tasting & Cultural Walking Tour, I explore the city with Key West Food Tours. When we pass an unremarkable house with a sidewalk kiosk, I am transported back home and back in time.

Our guide tells us this was once the place for fresh seafood because Tomasita sold the fish her husband caught, just as my mother had prepared fish my father brought home.

Standing before the little kiosk, I think about the simplicity of humankind’s relationship with the oceans, which sustain us and deserve the stewardship I’ve discovered from one end of the Overseas Highway to the other – the kind of stewardship that fosters the renewed hope for the oceans that the Keys has given me.