A dozen whales catapult into each other a few hundred feet away. “The whales are putting on a show,” our guide, Zeke, hollers from his kayak as another breaches nearby. Every winter, North Pacific humpbacks breed in the warm waters off western Maui, and even though Zeke’s been leading these tours for years, his voice still trembles with excitement. “Because it’s the end of the season, the males are posturing to woo the females,” he says.

“They’re flexing,” says my 14-year-old son, Kai, with a whoop.

“All of those whales are fighting for one girl?” my 10-year-old, Nikko, asks.

Zeke straightens his safari hat and explains that the males often battle to escort a mom and calf back to Alaska with hopes of mating.

Though I appreciate the dramatic show (a bit too close for comfort), the whales are a bonus on our excursion. I booked with Hawaiian Paddle Sports because they use proceeds from these winter whale watching and summer snorkel kayak adventures to fund Maui conservation projects, such as clearing invasive pickleweed, restoring ancient fishponds, and cleaning up beaches.

We came to Hawaii to test out the Aloha State’s regenerative tourism mission – one of the planet’s first major destinations that uses tourism to better the destination. Regenerative tourism isn’t about travelers thinking up what they will do to help. Rather, guests heed guidance from the local (often Indigenous) community on how to make holistic, truly regenerative choices. I was hoping we could also have some fun in the process.

What Is Regenerative Travel

According to Anna Pollock, a UK-based regenerative travel expert, travelers should consider the true impact of their entire journey. This holistic approach can feel daunting at first – how many of us can figure out the emissions of a hotel’s imports or how they source their water?

But she recommends that explorers start small. Maybe choose to stay at a locally owned and operated hotel (not a vacation rental) that’s actively working to minimize their negative environmental impact on the land and the community.

Hotels can also be a preferred option because the rise in vacation rentals raises housing costs that, in turn, pushes out locals. Or eat only at locally owned restaurants sourcing produce from Hawaii’s organic farms. Another option would be to participate in activities owned and operated by Hawaii residents, such as our Maui kayak trip, that use your money to fund beneficial activities like educational experiences for the island’s children.

For years, I’ve been reporting on Hawaii’s transformation from a tourist playground to a more environmentally responsible (and social justice-minded) destination. In a recent conversation with Kalani Ka'anā'anā, chief brand officer at Hawaii Tourism Authority (HTA), he explained that Hawaii residents have long been growing uncomfortable with tourists hiking through sacred places, trashing natural spaces and making it nearly impossible for local family beach gatherings on weekends.

So HTA invited locals to help rethink tourism. Communities envisioned and helped implement dozens of solutions, ranging from a statewide ban on non reef-safe sunscreen to reservation systems at overrun spots like Oahu’s Hanauma Bay or Kauai’s Haena Beach Park.

Locals were weary of people coming to the islands expecting aloha (love), without offering it in return. Ka'anā'anā says, “You wouldn’t show up for dinner at someone’s house empty handed.” So HTA began offering experiences for visitors to bring their own aloha to the Aloha State.

How To Participate in Regenerative Tourism

In Hawaii, the easiest way to participate is with the Malama Hawaii program. Malama Hawaii kicked off during the pandemic initially to support local businesses. Hotels offered discounted stays for visitors who agreed to participate in stewardship activities like planting trees or restoring native fishponds.

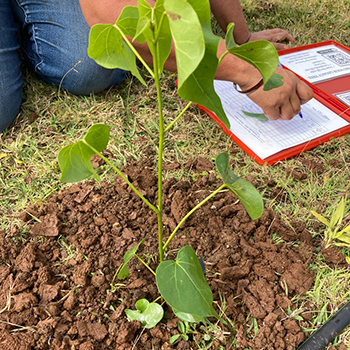

To offset the emissions from our California flights, my family travels to the North Shore of Oahu to plant native milo and koa trees at Gunstock Ranch in partnership with the Hawaiian Legacy Reforestation Initiative. A forest of native seedlings planted by major corporations and regular folks like us houses honeycreepers, or amakihi, singing from the thickening branches.

Because my aim as a traveler is to do more good than harm – different than simply being sustainable or leaving the place as it was when you arrived – tree planting isn’t enough to make our journey regenerative in scope.

So, during the planning stage, I signed up for a Malama Hawaii volunteer day on the shores of Pearl Harbor to help restore an ancient fishpond. During the monarchy, Native Hawaiians had lured small fish into a pond enclosed by lava rock, feeding them until they were too big to escape. Back then, fishponds were comparable to the local fishmonger.

On the volunteer day, we gather under the penetrating sun with local scientists, students, veterans and teachers to remove invasive pickleweed from the muck. I’m concerned that my family will get fatigued from manual labor with no shade, but little Nikko is a beast. He doesn’t want to stop, even for a homemade lunch of katsu and poi (taro root pounded into a paste).

After lunch, we stand on the shore feeding leftover Hawaiian sweet bread and watermelon to the bass with Aunty Kehau, or Kehaulani Lum, the person responsible for this restoration project. Nikko asks if he can return tomorrow, saying this is the best thing he’s ever done in Hawaii – and that’s saying a lot from a kid who visited every island when I researched Hawaii guidebooks. Aunty Kehau gathers her long, graying mane off her shoulder and says he is welcome anytime.

On the drive back to Waikiki’s locally owned and operated Kaimana Beach Hotel, I wonder why weeding with a bunch of adults speaks to my son. Was it, as Aunty Kehau said, that kids enjoy being a part of community, feeling useful and learning experientially – all tenets of how travel can inspire us? Nikko says, “I loved this because no one was lecturing about the problems; they just invited us in to help. And we did. And it was fun.”

How had I never realized that the most impactful travel experiences could give back? When we curate trips that offer something of ourselves, we receive so much more than a flower lei and directions to an overpopulated beach.

Changing Through Regenerative Travel Experiences

On Maui, we head out on a snorkeling trip with Trilogy, a popular catamaran company known for their educational excursions. Once a month, they offer a Blue Aina tour (a snorkeling/reef cleanup).

Cleanup kits affixed around our wrists, we search for the Hawaiian state fish, a humuhumunukunukuapua'a, and trash – which to my delight, I find none, a positive sign of other earlier cleanup measures.

Looking more closely at the reef, I finally see the little black, blue and yellow fish pecking at a sea anemone as well as an eel slithering behind a faded rice coral, and though some of the coral has suffered bleaching (a result of a warming ocean and pollutants like the chemicals in our sunscreen), a lot of the reef remains vibrant.

Back on the boat, our captain, Riley, explains that traveling opens us to new experiences. In that openness, we can change. Exploring the living reef with locals educates us and offers the opportunity to give back (with our money) to the people who are protecting the ecosystem. It may seem simple, but it’s regenerative.

On our last day in Maui, we visit Napili Bay, a popular cove with vacationers. A couple of children toss dried coral into the waves and their mother looks on, unphased. “You can’t throw coral,” I say, “they’re alive.”

The mother bumbles through an excuse saying someone told her it was OK if they were small. Kai sees my face redden and explains that even coral that looks dead can be home to living things – that’s how it regenerates.

The mom shrugs her shoulders and leads her girls away, saying they’ll have more fun in the pool. Kai then races up to the sand to throw away plastic that he found on the seafloor.

One aspect of this trip I didn’t expect was how positively it would impact my kids. Now, Kai charges back into the sea, hollering, “Race you,” before leading me out into the bay.