As an aquatic wildlife diversity coordinator for North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission, Luke Etchison’s job requires a lot of fish surveys. That entails pulling on a pair of goggles (and, in the cold months, a wetsuit) and floating contently along in some of the state’s most scenic rivers.

One of his favorite creatures to spot is the tangerine darter, a long skinny fish he calls an “8-inch orange popsicle.” For a long time, Etchison lamented that only he and his colleagues ever laid eyes on the fluorescent fish – and not just because it’s stunning. “If people don’t see it, they won’t care about it,” he says, “and people never see the things we’re trying to conserve.”

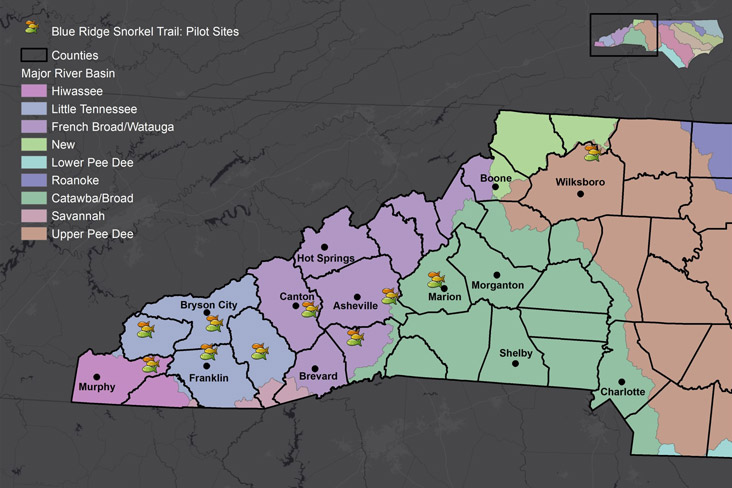

When COVID-19 hit and the rivers where Etchison works were suddenly teeming with people looking for pandemic-safe fun, he saw an opportunity to address the disconnect. He and his colleagues created the Blue Ridge Snorkel Trail, a choose-your-own-adventure assortment of 10 sites on nine different rivers that wind through the mountains of Western North Carolina.

Last summer, more people than ever were able to watch crawfish burrowing into muddy banks and logperches flipping over rocks in search of food (and, yes, admire the colorful tangerine darter).

But freshwater snorkeling is catching on in waters far from the Blue Ridge. From the cold coastal streams of the Pacific Northwest to the crystalline springs of the Sunshine State, intrepid inlanders are discovering foreign worlds in familiar bodies of water.

“Even if you go to the same river every day, you’ll see something different and learn something new every time,” Etchison says. “It’s an infinite world of exploring and connecting.”

The Blue Ridge Snorkel Trail

One of the best things about freshwater snorkeling, according to Etchison, is how inexpensive it is. While his agency was ready to hand out masks and goggles at last summer’s kickoff events, almost every attendee came with their own equipment. “All you need is a swimsuit and some cheap googles,” he says, and most people have those things tucked away in a pool or beach bag.

While the mountain streams can be a little chilly, you’ll soon forget any momentary discomfort, says Etchison, “especially if you’ve never seen a fish do its thing underwater.” And if the cold gets to you, you can always don a wetsuit.

One of the aquatic creatures you could spot is the greenfin darter, a tiny fish that snorkelers may see duking it out for territory. “When they get upset, they have a hormonal response that produces these temporary black bands on their sides,” Etchison explains. “You really get a whole different perspective on how cool and unique they are.”

Signage at each site educates visitors about which species they’ll encounter as well as conservation efforts for that particular watershed. Snorkelers often keep their eyes peeled for Eastern hellbenders, one of the largest salamanders in the United States.

These slimy creatures can grow up to 2 feet long and go by various nicknames: snot otter, lasagna lizard, water dog, to name a few.

The number of Eastern hellbenders is currently declining, according to a 2023 article published in Global Ecology and Conservation. Moreover, the population will be further impacted over coming years, the authors report, due to the changing climate, loss of habitat and other stressors.

Etchison hopes that inviting people into the salamander’s habitat will inspire more investment in freshwater conservation. “If we don’t look under the surface, we can quietly lose things and not know we ever even had them,” he says.

Eleven new sites are expected to be added to the trail in 2024, including one in Virginia. Etchison says plans are also underway to create trail sites in Georgia and Tennessee, so that even more snorkelers can peer beneath the surface.

Photos: Luke Etchison

Snorkel USA

While Etchison counts himself lucky to live near such clean mountain rivers, the fish biologist knows firsthand that all waterways have their charms. “I grew up on a farm in Indiana,” he says. “Even in the middle of the Corn Belt, there were still really cool fish to see,” he says.

Kimberly Winter would certainly agree. As the former national program manager of the U.S. Forest Service’s NatureWatch, Winter has helped develop freshwater snorkeling programs across the country.

In Florida’s Ocala National Forest, snorkelers can say hello to blue tilapia, bluegill, bowfin and longnose gar.

In the highlands of Monongahela National Forest, snorkelers can admire the rainbow and brook trout that draw scores of anglers to West Virginia’s mountain streams each year.

“But instead of yanking a fish out of the water and looking at it in distress,” says Winter, “you are in the water in that animal’s own home environment, feeling what it’s feeling and hearing what it’s hearing. All without intruding on it.”

In Oregon, Kristen Daly, the youth education program manager for the Calapooia Watershed Council, worked with the Forest Service to create the first freshwater snorkeling program west of the Rocky Mountains. Every summer, she introduces field trips for kids from a local residential shelter to the aquatic wonders of Willamette National Forest.

“The hardest part of the day is getting the wetsuit on,” she says. “But then the kids love seeing sculpins with their fat heads and skinny tails and, of course, cutthroat trout and salmon are super special, though we are always careful to avoid spawning grounds.”

For Daly, though, her favorite snorkeling sight isn’t the fish. “To see kids with such weight on their shoulders come out and play in the river and just be a kid for a while, it’s very special,” she says.

Unlike the Blue Ridge Snorkel Trail, which directs participants to specific sites, the Forest Service doesn’t provide exact coordinates for where to snorkel. “If we get a bunch of people in one place sloshing around, we could have some pretty serious negative impacts to the resource,” Winter explains.

Instead, the agency invites would-be snorkelers to explore their own nearby forests. Or as Daly advises: “Just go stick your face in the river!”

Snorkel – and Protect – Your Watershed

If there aren’t any established snorkeling programs near your home, that’s not a problem. Freshwater snorkeling is possible virtually anywhere there’s clean water. But making sure nearby creeks and rivers are truly clean enough to be safe to splash around in may take some effort.

“Seek out your local waterkeepers,” says Etchison, referring to nonprofit organizations that monitor water quality in their community. “They will be able to point you to clean water.”

Etchison also recommends investing in a good wetsuit, especially if you find yourself wanting to stay in the water longer or extend your snorkeling season into the fall and spring.

As for where to find the most action underwater, he says to stick to the shallow sections. “Big fish tend to hang out in the deep end, and they usually scare other fish away,” he says. “Plus, it’s safer in shallow water; you can simply stand up if you need to.”

Winter has more good advice: “Just float – don’t go after the animals. Let yourself be one with the water and see who comes to you,” she says. “Also, be sure not to mess up the rocks, not to disturb the habitat.”

While snorkeling is about having fun, it should also be a good reminder of why taking care of our rivers, streams and creeks is so important. “If there are bodies of water near you that aren’t clean enough to put your face into, remember the animals have no choice,” Winter says. “So get involved – join a river cleanup; join your local conservation groups; and be an advocate for clean water.”