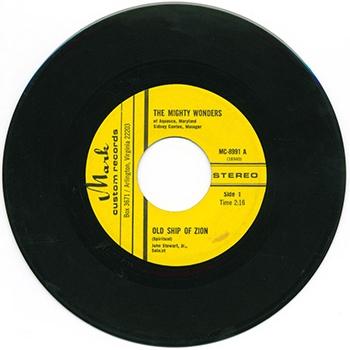

It was a few days after the Grammy Awards in 2005, and Baylor University journalism professor Robert Darden was worried. He had been happy to see gospel legends Mavis Staples and the Blind Boys of Alabama perform “Jesus Walks” with Kanye West and John Legend, a collaboration fueled by the boom of contemporary gospel. But as new gospel was prospering, the genre’s foundational music – songs such as “Old Ship of Zion” recorded in the early 1970s by The Mighty Wonders of Aquasco, Maryland, and many others before them – was becoming nearly impossible to find.

Darden, who had recently published a book about the history of gospel, was often on the radio back then, doing interviews about his work. Each time, calls poured in from listeners eager to know where they could buy the classic tracks he was sharing on air. The answer: They couldn’t.

Almost none of the music from what’s known as gospel’s “Golden Age,” roughly 1945 to 1975, was recorded for major labels. Artists ordered perhaps a couple hundred copies of a record to sell at their performances, and that was that. “They were done in terrible little studios, and they were raw and they were real,” Darden says.

In 2007, with the help of a $350,000 grant from Charles Royce, chairman of Royce Investment Partners in New York, Darden founded the Black Gospel Music Restoration Project, a mission to find and digitize all the black gospel music recorded during the Golden Age. Today, the Royce-Darden Collection of audio files includes 14,000 songs and albums.

There’s always a backlog of records waiting to be recorded and cataloged at the Ray I. Riley Digitization Center in Baylor’s Moody Memorial Library in Waco, Texas. Shortly after the project began, Robert Marovich, a gospel music historian in Chicago, heard Darden on NPR’s Fresh Air and began lending about 50 vinyl discs a month. Approximately 6,000 records later, “we have not yet gone through his 45 collection,” Darden says.

Other records arrive in the mail from people who have heard about the project through Darden’s interviews or appearances.

Darden grew up listening to gospel. As the son of an Air Force colonel, he lived alongside black families at bases around the world. “If [my friends] were in my parents’ house, they’d be hearing Perry Como and Andy Williams and movie themes. Mom loved movie themes. And if I was in their houses, I’d hear this extraordinarily exciting, vibrant, rhythmic music,” he says.

To access the gospel music collection, visit the Black Gospel Music Restoration Project at Baylor University.

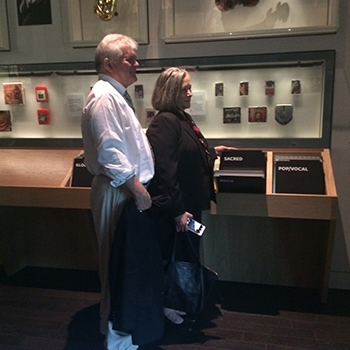

Darden has now published three books about gospel music and is writing a fourth, based on the life of the late gospel singer Andraé Crouch. When he and his wife, Mary, travel, they scour thrift stores, estate sales and used music shops for Golden Age gospel, loading their 2013 Subaru Forester with boxes and crates of records. They’ve already put nearly 100,000 miles on the vehicle. They’re also, as of last year, the owners of a 2021 Outback.

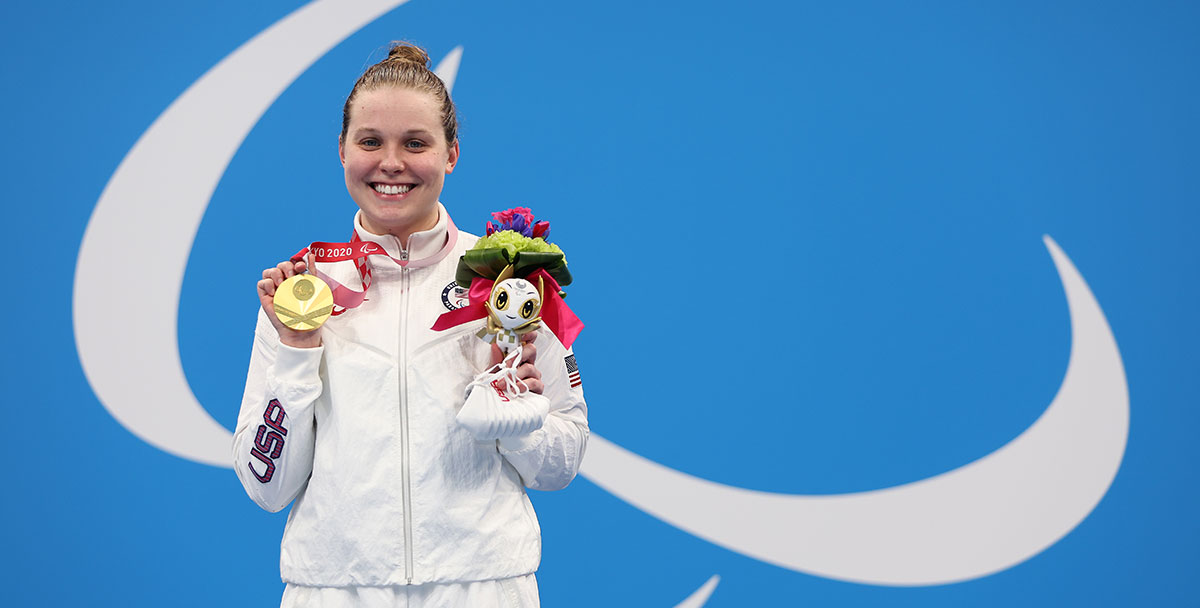

The Black Gospel Music Restoration Project is also part of a permanent exhibit in the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. Visitors can listen to songs such as the “Old Ship of Zion” and learn more about the important role gospel music played throughout the civil rights movement.

Back on the Baylor University campus, the records keep coming. “I don’t know if [we’re at] 10%, 1%, 20%,” Darden says of the number of tracks he’s digitized compared to what’s out there. “We don’t have any idea how much more there is.”

Know someone who’d make a great fit for an Owner Spotlight? Visit Dear Subaru and use the story title “Owner Spotlight.”