By the time I park my car in a deserted pullout at Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, the juniper trees are already casting long shadows across the dusty road.

Sunset is almost here, I think, feeling tired after a day spent exploring Bryce Canyon, the national park in southern Utah. Even on a weekday, the canyon had been crowded. Rubbing shoulders with other tourists, my girlfriend and I had to jockey for photos of the park’s sandstone towers, thousands of pink and orange rock columns standing side by side too proud to surrender to gravity and fall to the valley floor.

Now, at sunset, we have entered a different world. There are no crowds here in Grand Staircase, a sprawling park about 20 miles southeast of Bryce. We throw our tent down in the sand and fall asleep to a distant coyote’s howl and the supreme silence of being far away from any other human.

I never planned on spending much time in the Grand Staircase – that first night we were only looking for a free place to sleep. “Remember, you can camp pretty much anywhere on BLM land!” a friend had emailed me in reference to the U.S. Bureau of Land Management, which manages the park, when I asked for camping recommendations. (For more on camping on BLM land, see “Tips for Bureau of Land Management Camping” below.) But that night in Grand Staircase wasn’t just an insignificant stop. It was the kindling of an obsession.

Experience Black’s trip for yourself – check out his stops on Roadtrippers.

My first encounter led to a second visit, then a third. Each time a trip ended, my list of things to see and do was longer than when I had arrived, the park always seeming to offer another arch to find, more dirt roads to navigate, more starry nights to see and vistas to take in, and more slot canyons to squeeze through.

Eventually, Grand Staircase changed from being just a free place to stay – a layover between other, more famous national parks – to the destination itself.

Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument sits in the center of Utah’s national park country, bordered by Bryce Canyon National Park to the west, Capitol Reef National Park to the northeast and the Colorado River to the south. Its scale is unlike any of Utah’s national parks, with about 1 million acres of land. (The U.S. Department of the Interior reduced it from nearly 1.9 million acres under a 2017 executive order.) For reference, Bryce Canyon is over 35,000 acres.

The park gets its name from the Escalante River and the colorful ascending layers of sedimentary rock, the so-called “Grand Staircase,” that stretch across southern Utah and Arizona, ending at the Grand Canyon’s North Rim. The monument’s land is some of the most remote in the lower 48.

It was one of the last places in the continental United States to be mapped by the federal government; it was literally shown as a blank space on government maps until 1872. And thanks to BLM’s public-use policies, you can pull your car over to the side of the road and camp just about anywhere you would like – no reservations or permit required.

Scott Berry, a retired attorney who serves as vice president of the board of directors for Grand Staircase Escalante Partners (GSEP), a nonprofit that works to preserve the monument, first fell in love with the area while driving his Subaru through the land in the 1970s, well before the area was designated a national monument.

Over the years, he’s upgraded his Subaru – his latest model is a 2015 Outback 3.6R Limited – but he keeps driving in the same place, forever entranced by the desolate beauty of the area.

“It is a remote and lonely place on purpose,” Berry says. “In Escalante, you can go to an arch and you’re likely to be the only person there. You don’t have that feeling when you’re sharing something with 300 or 400 of your neighbors standing around taking Instagram photos.”

Despite the park’s rugged terrain, there are many areas that you can visit in a standard vehicle. I once rented a car in Las Vegas and navigated Cottonwood Canyon Road, which bisects the park. I was able to see Grosvenor Arch, a 150-foot-tall double arch made of sandstone; hike through the winding red rocks of the Paria Box; and camp in the beautiful Paria River Valley.

The river is surrounded by hills covered in boldly colored rocks, a fanciful layer cake of purple, blue, pink and red. The fact that I was camping for free in front of this scene made its colorful brilliance all the more astonishing.

Native tribes, or Ancestral Puebloans, the name preferred by present-day Native Americans to describe their ancestors in this area, have lived on the land we now call Grand Staircase for thousands of years. They farmed squash, corn and beans; made distinct red, black and white pottery; and built multistory homes of adobe and stone, a replica of which can be seen at Anasazi State Park in Boulder, Utah.

Davina Smith, a member of the Diné (Navajo) tribe, says that all visitors to the Grand Staircase should know that they are walking on sacred native lands that are still used by indigenous people to perform traditional ceremonies.

“Not only is it an area for recreation, for a place to come and explore, but it’s also a place to get a deep-rooted understanding of why tribes are connected to these areas,” says Smith, who is also on the GSEP board of directors.

Smith encourages visitors to research the area’s native history before they arrive and to learn more at the monument’s visitor centers. “Education gives that perspective to know that these lands are indigenous, and we’re still here.”

The more time I spend in Grand Staircase, the more I respect how difficult it must have been to create a flourishing life in these often inhospitable lands. Water comes rarely, but when it does, it can arrive in flash floods that turn a dry desert into a dangerous deluge in just minutes.

– Scott Berry

The morning after the first night in our tent at Grand Staircase, my girlfriend and I walk into the heart of Bull Valley Gorge, a magnificent slot canyon with all the slick rock and tight walls you would expect. We originally planned on driving to another park, but we cancel our plans instead and take on Hole-in-the-Rock Road, a 62-mile dirt road that cuts across the rocky eastern portion of the park.

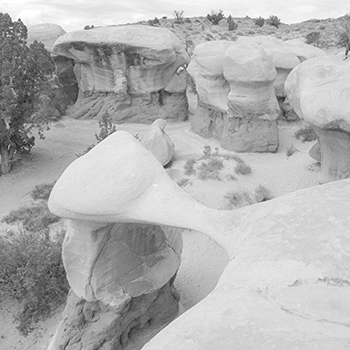

We stop at the Devils Garden, where dozens of hoodoos and cartoonish natural arches formed out of smooth sandstone look like a real-life Flintstones set. On foot, we squeeze our way through the ridiculously tiny Peek-a-Boo Slot Canyon. We take our time, camping where we want to, walking into the desert when we want to.

The beginning of the road, just outside the town of Escalante, is one of the park’s few areas with crowds, but before long we’re alone once more. The road gets worse. I hear rocks scrape under my SUV and drive over deep ruts that send one wheel into the air and then another.

I get nervous and think about turning around, but keep going until finally my clammy hands can let go of the steering wheel as we park on top of a 2,000-foot-tall sandstone bluff, staring at the impossibly azure water of Lake Powell.

It’s like finding a treasure I didn’t know I was looking for, seeing all that water after spending days driving across dry red rock. I feel that rare feeling that somehow comes so easily in the Grand Staircase: I’m on a road trip. I’m on a journey. And I can’t wait to come back and do it again.