The midday Wisconsin sun glimmers off patches of snow as I hike uphill through the forest. The land here in Lodi, a small town less than 30 miles northwest of Madison, is a series of upward and inward twists and turns you don’t typically see in the Midwest.

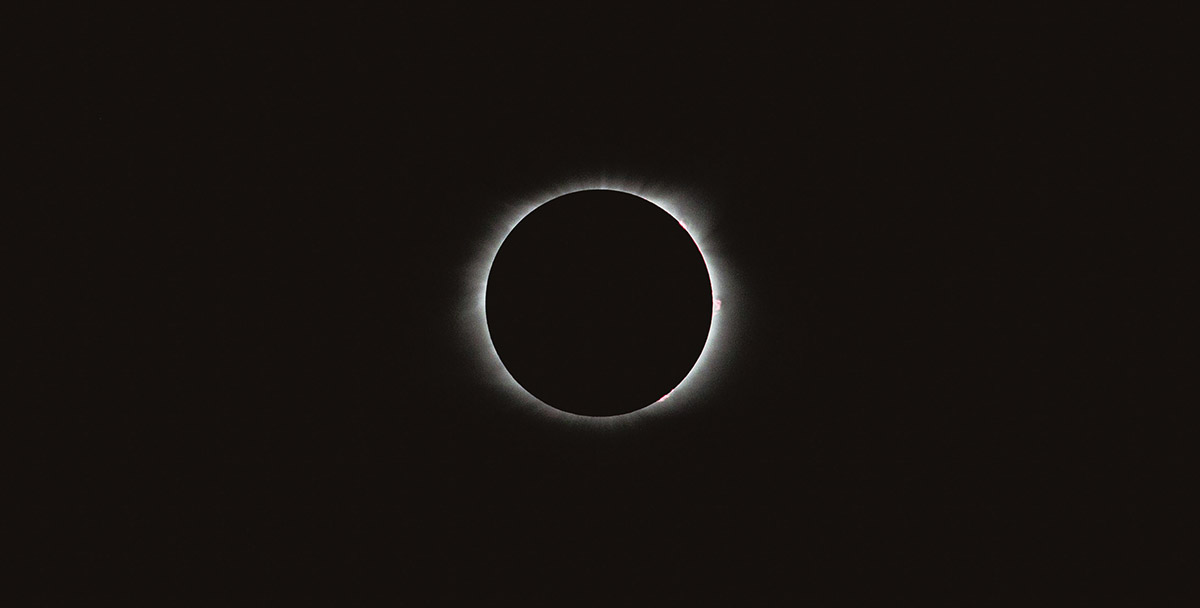

I’m exploring the Ice Age National Scenic Trail, one of just 11 trails in the United States that has been given the National Scenic Trail designation by the National Park Service. More than 12,000 years ago, receding glaciers carved out the rise-and-fall terrain that attracts hikers, runners and snowshoers. Across more than 1,000 miles of trail, there are easy 1.2-mile stretches, gruelingly rugged 14.5-milers and everything in between.

Earlier today, I drove over 2½ hours from Chicago to Lodi to meet Melanie Radzicki McManus, a journalist and runner who wrote the book Thousand-Miler, about hiking the Ice Age Trail. In 2013, McManus ran and hiked 1,100 miles in 36 days, then the fastest time logged by a female athlete. In 2015, she repeated the feat in just 34 days. As a former collegiate rower, I understand her drive. No surprise that we chose the more difficult of the two hikes that start at the Lodi trailhead, a 3.1-mile upward climb through the trail’s Eastern Lodi Marsh Segment.

Like a black-and-white photograph, the bright snow contrasts the dark birch trees along the trail. Except for a few geese squawking in the distance, it is breathlessly quiet. After having a child 2½ years ago, the silence is strange. I haven’t heard this much stillness in what seems like forever. I feel at peace.

Growing up, I spent summers hiking a cedar-lined path around Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin, where my grandmother had a home. It’s still my favorite respite. As a working mother who had a difficult pregnancy – I was diagnosed with lymphedema, a genetic disease that causes your body to painfully swell – and a NICU baby who’s had a lot of allergies, it’s been a gauntlet. I’m always taking care of someone or something else, and there’s never enough hours in a day. This trip is the first time I’ve taken a break for myself, by myself, in years.

McManus, a mother of three, understands. She started hiking during a 2009 trip to Spain’s Camino de Santiago. With a child in high school and two in college, it felt like an escape. When she returned to Wisconsin, a friend told her about the Ice Age Trail. “The first time I hiked here, I thought I knew Wisconsin, but I realized I didn’t,” she says. “There’s so much beauty, but you just pass by it unless you hike the trails.”

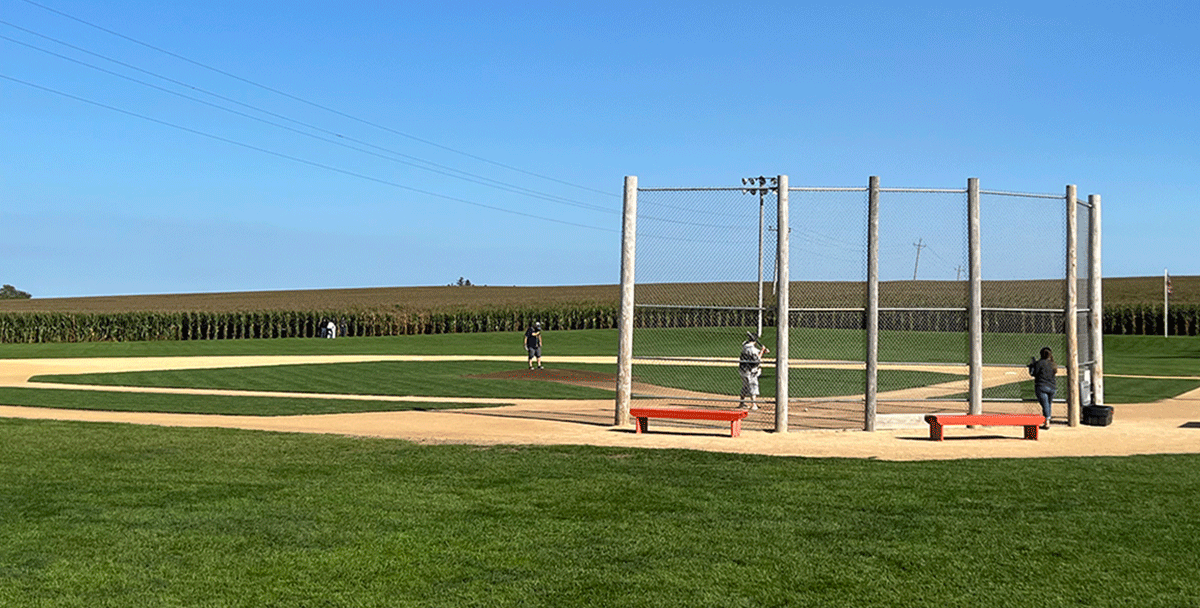

We climb steeply for a half-mile, following yellow blazes (arrows on posts or hash marks painted on trees). A ridgetop offers a clear view of hills and valleys, mounds of earth and bluffs between stretches of prairie and frozen marsh. Feeling a kinship, we discuss our shared connection to Sheboygan, Wisconsin – my father’s hometown, and where McManus spent her middle and high school years – and promise to keep in touch.

I drive an hour east through farmland to the Westphal Mansion Inn Bed & Breakfast, a beautifully restored 1913 English tudor in Hartford. It’s the perfect place to relax before tomorrow’s adventure: snowshoeing with Jackie Scharfenberg, a naturalist for Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources’ Bureau of Parks and Recreation Management in the Kettle Moraine State Forest, Northern Unit.

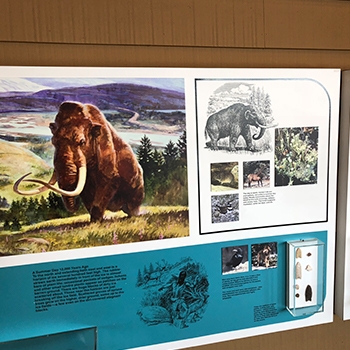

Scharfenberg and I meet at the Henry S. Reuss Ice Age Visitor Center in Campbellsport, 25 miles northeast of my hotel. Inside, a woolly mammoth mural greets me, along with displays of rocks and fossils and a small gift shop that rents snowshoes for $5.

Outside, Scharfenberg gives me a history lesson. The glaciers in Wisconsin were nearly a mile thick, she says. When the ice melted, it created potholes, called kettles, and piles of dirt and stones – usually in ridges – called moraines.

In the 1950s, a Milwaukee lawyer, Ray Zillmer, envisioned a national park following these glacial landforms. He created a foundation, now the nonprofit Ice Age Trail Alliance, which, in partnership with the National Park Service and Wisconsin DNR, enlists volunteers to help with trail maintenance and purchases land to connect disparate segments of the trail.

Unlike the Appalachian Trail, the Ice Age National Scenic Trail is not fully connected. You can thru-hike it from one end of the state to the other, but sometimes you’ll be spit out onto a road and have to find where the trail picks back up. The ultimate goal of the Ice Age Trail Alliance and its partners is to unite all 1,200 trail miles.

Scharfenberg and I head to Butler Lake Trail, where we climb a snowy staircase to the top of Parnell Esker, a 4-mile serpentine ridge. “If you can walk, you can snowshoe,” she tells me. “Just pick up your feet and march.”

We climb up and down, snaking through forests of birch, ash and ironwood trees. In the distance, a sandhill crane bugles a call and an owl hoots. A small robin sits on a tree. We are the only ones on the trail today. Walking through a tunnel of trees, it feels like I’m in a cocoon of nature.

I spend the night at The Fig & The Pheasant, a welcoming 19-room hotel in neighboring town Plymouth, and the next morning, I hike more than 2 miles on the trail’s LaBudde Creek Segment in Elkhart Lake. Although I’ve liked the company, it’s refreshing to be on my own. I walk through grasslands and wetlands that morph into forests of cedars and wild sumac.

After a quick lunch – a grilled ham and gouda to-go at Off the Rail, a counter-service spot in Elkhart Lake – it’s time to meet Annie Weiss, a 35-year-old ultramarathoner, and her husband, Brian Frain, at the trail’s West Bend Segment.

In 2018, Weiss set the fastest Ice Age Trail time, breaking McManus’ previous record as well as the men’s record of 22 days held by Jason Dorgan. Weiss clocked in at 21 days, 18 hours and 7 minutes. She held the record until June of this year, when ultrarunner Coree Aussem-Woltering finished just a few hours faster: 21 days, 13 hours and 35 minutes.

Weiss, who grew up in Milwaukee, has been running portions of the Ice Age Trail since 2011. She loves the terrain and is surprised by how often she meets people who have never heard of the trail. “It’s shocking,” she says.

The trail is a place “to disengage and be quiet,” Weiss continues. “It’s a way for me to disconnect from the city and reconnect with myself,” she says. “You find peace on the trail.”