In 2019, my husband, 5-year-old son and I attended our northern Kentucky community’s Earth Day celebration in the park. We left with a tiny milkweed seedling as a memento. Milkweed is the only host plant for monarch butterfly caterpillars. Every year monarchs seek out this plant to lay their eggs.

Still, I didn’t expect much from our little plant. We had just closed on our 1926 home on a quarter-acre lot. The property was all grass with a few mature trees and no garden. I had little hope of attracting butterflies.

I like a lush, inviting yard. Grass? Not so much. Grass isn’t “green” – it’s wasteful, costing homeowners time, money and energy in an endless cycle of planting, watering and cutting.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates that landscape irrigation accounts for nearly one-third of all residential water use, totaling almost 9 billion gallons per day. Grass is actually considered America’s largest irrigated “crop,” beating out even corn, according to a study led by research scientist Cristina Milesi at NASA Ames Research Center.

Yet, our manicured lawns do little for humans or the environment. Grass prevents erosion, sure, but it doesn’t produce blooms that feed the pollinating insects that are so vital to our food systems. And while grass, like other plants, converts carbon dioxide into oxygen, the benefit is offset by the maintenance: Harmful greenhouse gases go right back into the air when you run a lawn mower, pump water or spread fertilizer.

You have to wonder if it’s all worth it. My husband and I didn’t think so. We wanted something different, so we set out to transform our yard.

The Pollinator Garden

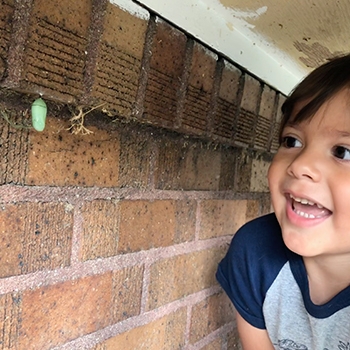

Something magical happened with that little potted milkweed plant after we placed it on our front stoop. It grew tall in its pot. Then, we discovered a caterpillar munching away on its leaves. Soon there were two, three and four. They were eating the milkweed down to the stick. My son and I were thrilled, and we promised to nurture these baby caterpillars through their metamorphosis. Adding a pollinator garden to our yard became top priority.

The idea is simple: Plant flowers from which butterflies, hummingbirds, beetles and bees can gather pollen and nectar that they subsequently spread to plants and crops – from tomato vines to blueberry bushes – helping them thrive.

But gardeners have to be cautious when buying host plants like milkweed. Some garden supply centers spray their plants with herbicides indiscriminately. For caterpillars, this can be deadly. It’s safer to buy from a greenhouse or a native plant sale at a nature preserve. To buy more milkweed, I ran to the local greenhouse.

For our garden, we chose the patch of lawn between our front door and the city sidewalk. It wasn’t much, but even a small space can make a good pollinator garden, says Scott Beuerlein, a manager at the Cincinnati Zoo & Botanical Garden® in Cincinnati, Ohio. “If we all just think about adding a little bit here and there, all of that can collectively create a corridor for pollinators,” he says.

Instead of tilling, we covered the front lawn with biodegradable garden paper and then added a layer of mulch to let the grass underneath decompose to feed our soil. After selecting our plants, we again chose not to till and instead dug one small hole for each plant. This helps leave bug larvae in the dirt undisturbed and also minimizes the spread of weeds. Remember: Every time you break up the soil you make a perfect planting place for those weed seeds that are blowing in the wind.

Managing Stormwater

Green infrastructure is the practice of keeping as much rainwater as close to where it falls as possible. Runoff from downpours causes erosion, floods basements and carries pollution from roadways into our water supply.

Using simple kits we found online, we connected and placed four 60-gallon rain barrels at the bottom of our downspout at the back of our house, and one more decorative barrel at the downspout in front. We use the water collected in rain barrels for our gardens and indoor plants. The EPA estimates that rain barrels save homeowners about 1,300 gallons of municipal water during the summer months of high water usage.

Green Space

To avoid a turfgrass lawn but still give our dog and son space to run and play, I turned to a plant that’s seeing a resurgence: clover. Before the 1950s, grass seed mixes always included clover. It’s drought tolerant, green year-round and isn’t picky about soil quality or sun exposure. It doesn’t turn yellow and die when exposed to pet urine, and its low-growing flowers feed the bees. It also, unfortunately, became thought of as a weed as more people turned to chemicals to maintain their lawns.

“The weed and feed products used to kill dandelions also killed clover,” says Jeff Lowenfels, America’s longest-running garden columnist, who has written weekly for the Anchorage Daily News since 1976. But lately, he says, he’s seen renewed interest in the once-spurned legume.

Growing a clover lawn was just the environmentally friendly solution my husband and I were looking for. To plant our clover, we aerated the yard with a rolling aerator – picture a push mower but with spikes that poke holes in the dirt – and tossed seed across the area.

If you plant only clover, you never have to mow it. It stays low to the ground on its own. You can even plant clover as a “living mulch” in your pollinator garden to fill in between your perennials and keep the weeds out. The only potential downside is that clover stains are a little harder to get out of clothes. But that’s why kids wear play clothes.

Though our family is revamping our entire quarter-acre suburban lot, you don’t have to overhaul your entire property to make a difference. If you can’t part with your grass out front, try a clover patch in the back. A pollinator garden can be a few pots on a stoop. Just recognize that your space – whether it’s a sprawling yard or a city balcony – is all potential habitat.

To find out how you can transform your outdoor space into a haven for pollinators, read “How To Create a Pollinator Garden in 5 Steps.”