One of Thomas Coyne’s scariest incidents happened while on a day hike with friends in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada. After climbing up to the top of a flat boulder with cracks in a number of places, “I heard what sounded like 100 rattlesnakes,” says Coyne, who’d accidentally climbed onto a rattlesnake nest.

“I had to stay as calm as I could. I took high steps and ninja walked over the rest of the cracks as I slowly backed off the rock.” Luckily, he didn’t get bitten. “But I was so freaked out that when I got to the trail, I sprinted for 100 yards.”

As a professional survival instructor, Coyne, the founder and chief instructor of Coyne Survival Schools in California, has trained many military operators on wilderness survival – from U.S. Navy Search and Rescue personnel to U.S. Marine Corps Mountain Warfare Training Center Marines – so he knew how to respond in a way that de-escalated the danger.

My experience with rattlesnakes, thankfully, has been more limited. I’ve hiked Caprock Canyons State Park in west Texas, where rattlesnakes are plentiful among the colorful canyons and steep bluffs. On one occasion, my aunt and I had to back away and take another path when a rattlesnake was spotted on the trail.

Like Coyne, I’ve learned that a day hike can pose more risks than an extended journey simply because it’s easier to head out unprepared when you assume you’ll be back to civilization in a few hours.

“Even if you don’t plan to be out there overnight, just being on the trail can mean anything can happen and it could take hours to reach help,” Coyne says. “People who are most likely to be injured or killed are people that just went out for a day.”

Many hikers head out too late in the afternoon without a first-aid kit, enough water, food or a map. Some only wear flip-flops, which is about as good as going barefoot. “Too many people just go in because they hear it’s a cool place,” says Rick Harding, a veteran hiker who works as a virtual outfitter for REI in Atlanta, “and then they get lost.”

Even if you have basic supplies, unexpected things can happen. Here are safety tips from outdoor experts so you don’t get caught unprepared.

Do a Test Run (“Shakedown”)

Before going out on a hike, carry all the gear on a walk around your neighborhood, suggests Emily Ford, the first woman to complete Wisconsin’s Ice Age Trail in winter. Called a “shakedown” in the hiking world, this test run is used to help you determine if your pack is too heavy and whether you need to leave anything behind.

Be Prepared To Stay Hydrated

Bring more water than you think you’ll drink – at least 2 liters (about 67 ounces) of water per person, says Harding – regardless of whether the weather is cold or hot. The general rule is a half liter of water for every hour hiked, he says.

It’s also a good idea to carry a small water filter that can clean water and ward off cryptosporidium, a microscopic parasite. “Get anything that is 0.2 microns filtration or better,” Coyne says. Options include the Sawyer® Squeeze Water Filtration System or a LifeStraw® water filter straw.

Be Able To Light a Fire in Wet Conditions

Stormproof matches are key. “Once you light them, they create their own oxygen so they can’t be put out,” Coyne says. “They burn underwater; they burn in the mud.”

Coyne also likes bringing fire-starter fuel cubes, which burn for over 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit for about eight to 10 minutes. “One of those cubes will get your hands warm or help start a fire even if you’re dealing with the pretty wet stuff” like damp sticks and branches, he says.

Be sure to completely extinguish any fire when it’s no longer needed to prevent a wildfire from starting.

Bring a Paper Map and Personal Locator Beacon

“I always bring a map in case the GPS dies,” Coyne says.

Know how to read a topographic map (also called a topo map), Harding says, because something may look deceptively close when it really isn’t. “That’s how people get lost or fall off cliffs,” he says.

REI.com offers a quick study with its article “How to Read a Topo Map,” or you can find one on hikingguy.com.

For backcountry hiking or those going it alone, consider a personal locator beacon. “You push a button, and it goes to a satellite,” says Coyne. “And you get rescued.” He recommends the ACR Electronics ResQLink™ 400 Personal Locator Beacon.

The way a locator beacon works can vary based on the device and technology used. In general, it pings your distress signal with GPS coordinates to a global network of satellites. The satellites send the distress signal to a Local User Terminal (LUT), which forwards it to search and rescue agencies, such as a county sheriff’s office, for help.

Have an Emergency Blanket and Kevlar® Cord

Pack a silver-sided emergency blanket, also called a survival blanket, that folds up to the size of a deck of cards. It’s windproof, waterproof and can maintain up to 90% of a person’s body heat or reflect the sun’s heat (if flipped silver side out), so it’s good for the winter or summer.

To convert the blanket into a shelter, bring strong, lightweight kite string. (Coyne recommends Kevlar cord that’s good for a 1,000-pound test.) “If you’re stuck overnight, it’s hard to build something from scratch,” Coyne says. “Having some string and an emergency blanket will be a lifesaver when you’re making a shelter.”

Bring More Food Than You Think You Need

“Always, always, always have a snack in your bag,” Ford says. “No matter what.” Even a mile hike could turn into something longer. “And you never know what’s going to happen,” she says. “Or maybe you’re having such a good time, you’re going to want to spend more time.”

The amount of food is subjective, says Harding, who recommends bringing high-caloric, shelf-stable snacks, such as trail mixes, granolas, nuts and runner gels. Eat a “good solid breakfast with plenty of carbs for energy and proteins for stamina,” he says.

Pack high-carb foods that are easy to digest and turn into sugars that burn quickly since a hiker generally burns 300-plus calories an hour on a sustained hike, depending on one’s weight and hiking speed. “Even Snickers® bars are good for instant energy,” Harding says.

Carry an Emergency Signal

The type of signal depends on the terrain and time of year.

All purpose: A Fox® 40 Whistle. Its loud, high pitch can be heard up to a mile away.

For open terrain: A small, unbreakable “signal” mirror can reflect in the air or on the ground within a line of sight for several miles. Coyne says smoke bombs are good to use in an open, snowy area where a big orange cloud can easily be seen.

For dense areas: A pen-style flare, such as the True Flare, screws on a small flare charge that shoots into the air above the tree line and is visible for close to 2 miles during the day and over 7 miles at night.

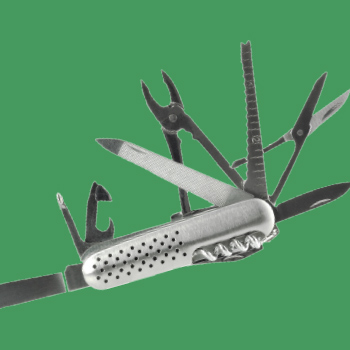

Get a Great Multitool

Ford always carries a knife with her, but she also sees the need for carrying a multitool. When she needed to remove quills from her catahoula-style dog, Zulu, who had a run-in with a porcupine while hiking, “having a multitool with pliers would have been immensely more helpful,” she says.

Ford likes a multitool that has pliers, a knife, a flat head and Phillips screwdriver and a can opener with a bottle opener. “Can openers are oddly sharp and can be used as a secondary knife,” she says. “You can always fix anything if you run into trouble.”

Coyne seconds that idea. He’s a fan of the Victorinox Swiss Tool that has helped him trim tree branches for a splint and carve dead wood into a friction fire-starting kit.

Follow Tick Protocol

To keep ticks away, the CDC recommends treating clothes and gear with 0.5% permethrin. Wear long pants and tuck them into socks or put duct tape around your ankles, Ford says.

When you’re done for the day, have a partner check for ticks or use a mirror to self-check. “The earlier you go hiking, the more likely the insects will be sleeping,” Ford says, “because a lot of times they warm up by the sun.”

Build Your Own First-Aid Kit

Adhesive bandages aren’t enough. Create a small but useful first-aid kit. “If anything does happen, you have to be your own first responder,” Coyne says.

Once on a 5-mile hike in Rocky Mountain National Park, Harding ducked under a pine tree and a branch pierced his baseball cap and sliced open his head. A clotting sponge quickly stopped the bleeding until he could get to an emergency room four hours later.

Besides clotting sponges, bring a painkiller like ibuprofen, Benadryl® for allergic reactions, gauze, medical tape, Bactine® to disinfect, nonstick dressings, antiseptic alcohol pads and insect repellent.

Coyne also suggests bringing a SAM® splint – a lightweight, flexible splint that rolls up into the size of a small pair of socks.

Learn Wildlife 101

Coyne’s advice: If a bear is spotted off in the distance and not coming toward you, don’t yell, just quietly move away sideways. If it’s lunging toward you, make yourself as big and loud as possible and they’ll likely scram.

Don’t play dead unless you’re being attacked by a grizzly bear or a brown bear, which are found in Alaska, Idaho, Montana, Washington, Wyoming and western Canada.

With black bears, the National Park Service advises escaping to a secure location like a vehicle or building, and if that’s not possible, fighting back with any object on hand. Target the bear’s face and muzzle using strikes or kicks. Consider packing bear pepper spray and use when a charging bear is within 60 feet of you.

When it comes to snakes, be wary of North American pit vipers – such as copperheads and cottonmouths – and other species of rattlesnakes. If you see or hear one, follow Coyne’s example: stay calm, back away slowly and then take an alternate path.

Most rattlers will bite on the hands, feet or ankles. If that happens, you’ll want to get to a hospital that can administer anti-venom as soon as possible. In the meantime, apply a light dressing to the puncture site, remain calm and don’t apply a tourniquet or take any painkillers that could cause blood thinning.

Dress Wisely for the Weather

Always check the weather in advance and be prepared for the overnight low. Don’t wear cotton, which stays damp with moisture. Opt for lots of thin layers made of merino wool, silk, nylon, polyester or synthetic materials that can dry quickly.

“As soon as you start to sweat, take a layer off or roll up your sleeves so your wrists are exposed,” Ford says, because the damp sweat can quickly cause hypothermia in colder weather.

Use a Headlamp at Night

“I’ve never been more thankful for a piece of equipment,” Ford says. Unlike a flashlight, it leaves your hands free. “You can use your trekking poles if you’re going down a steep face and [the light is] pointed in the direction of your eyeballs,” Ford says.

Always Let Someone Know Where You Are

If you’re flying solo, leave a note on the windshield about when you hiked in, with a date and time.

“If you get lost or something catastrophic happens, say you trip over a log and break your leg and can’t walk, the hardest thing to do is to find you if no one knows where you are,” says Abel Bean, the senior wilderness guide at the Teaching Drum Outdoor School in Three Lakes, Wisconsin.