I watched as the cow moose made its way along the shore of Wood Lake on Michigan’s Isle Royale, its head down as it nibbled at something I couldn’t quite see. Trailing nearby was her calf, looking as though it might topple over on its thin legs as it splashed in and out of the water.

I held still among the trees, wanting to avoid shattering the tranquility of it all. While the sight of foxes, hares, muskrats, beavers or wolves would have been usual for both mother and calf, coming across a human was far less common.

Isle Royale, the least-visited national park in the contiguous U.S., is a 206-square-mile island in the northwest of Lake Superior about 15 miles from the Canadian coast. The island is home to more than 2,000 moose. As for humans, just over 18,000 on average visit each year. (For comparison, the Grand Canyon gets more than 17,000 visitors per day.)

Part of that has to do with the three-hour boat ride from the docks on the northern reaches of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, or the need to rent private transportation, such as a seaplane. You can also arrive via ferry or seaplane from Minnesota’s Lake Superior coast, although whichever way you come, you’ll have to leave your vehicle on the mainland. Another factor behind its lack of visitation is that the park is inaccessible in the winter; it’s open only from April 16 to Oct. 31.

Watching the cow moose, I pulled out my cell phone and turned it on to check the time. I didn’t have to concern myself with missed calls or messages. My email wasn’t pushing notifications at me, either. No cell signals are available on Isle Royale, except for the occasional blip from a Canadian tower if you find the right elevation.

But that’s the draw to this remote place: solitude. Beyond the crashing of waves from the mighty Gitche Gumee (the Ojibwe name for Lake Superior) and the songs of various birds, the silence is almost deafening to those who are unaccustomed to such remoteness. There is no roar of engines because there are no roads. It’s rare to encounter large groups of people. Hunting is prohibited.

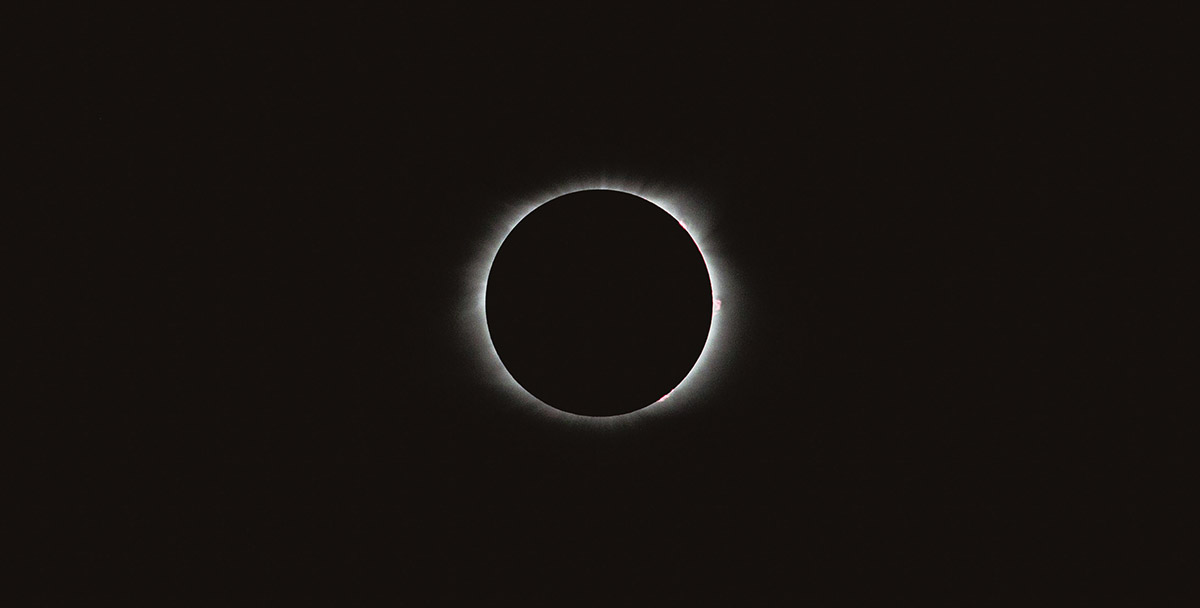

My preferred way to enjoy Isle Royale is fishing – there are around 40 different fish species to catch. But there’s plenty to do to pass the time. Hike over 160 miles of trails. Dive on one of the 10 major shipwrecks. Rent a canoe or kayak to explore the waters around the main island, the surrounding smaller islands and the inland waterways. And the stargazing here is second to none.

There are 36 campgrounds across the park, though the only guaranteed amenities at most are tent sites, a water source and outhouses.

If that doesn’t sound like your style, the Rock Harbor Lodge should be your base of operations; it offers indoor plumbing and even kitchenettes for longer stays. Rock Harbor is the center of activity in the park, home to the main visitor center, a general store, the marina, watercraft rentals and a small restaurant. Park rangers are stationed there and at three other ranger stations across the island.

Backcountry camping permits are also available, and many visitors explore Isle Royale through a cross-country camping foray. Unlike traditional camping, there is no worry about bears as there is no population in the entire park. However, you’ll still want to keep an eye on your provisions – foxes have been known to steal supplies in the night.

Even the signs of the people who formerly made the trek to live and work on the island have mostly been erased over the decades. Until the late 19th century, members of the Ojibwe tribes, who called the island Minong (which roughly translates to “the good place”), used it for hunting, copper mining and maple sugar gathering before Euro-American influences arrived and brought with them large-scale logging operations and mining.

While some evidence, such as the ruins of a long-abandoned copper mine, of those days can still be found – especially around Rock Harbor and some of the campgrounds – most of the land has been reclaimed by an abundance of nature.

You’ll find balsam, spruce, birch, aspen and ash growing along the shoreline, and shrubs such as bearberry, prickly rose and juniper in the rocky areas. If you get near the boggy areas, you’ll find leatherleaf, bog laurel, bog rosemary and Labrador tea, while the other wetlands are dominated by tag alder and sweet gale. In total, there are more than 600 species of flowering plants that range from small duckweeds to towering white pines.

More than 450 smaller islands surround the main island, all under National Park Service jurisdiction. Many of these satellite islands can be reached by boat, and some even offer campsites.

It’s possible to do Isle Royale as a day trip, but I recommend staying at least a few days. This is the rare place where you can immerse yourself in nature, disconnect from a connected world and, perhaps for the first time ever, truly be able to hear yourself think.